The State of the Railways in Kerala: Train Running Infrastructure

Trains have since their inception been synonymous with speed. Railways grew and flourished across the world because they reduced travel times, which were always expected reduce as technology improved. It is not so anymore. As we have already seen and quite famously quoted at many places, in India in general and in Kerala in particular, train speeds have actually decreased from what they were in the 1970s. The main reason for this is the massive increase in the number of trains as per the need of travelling public, while infrastructure in terms of track doubling, signalling technology, gauge conversion, etc had not kept up. This is especially acutely felt in a state like Kerala with its highly evenly distributed population density and thanks to under investment financially and policy-wise. The state simply does not have enough railway track to meet the demands of its growing and burgeoning population. And as we have already seen, this can be substantiated.

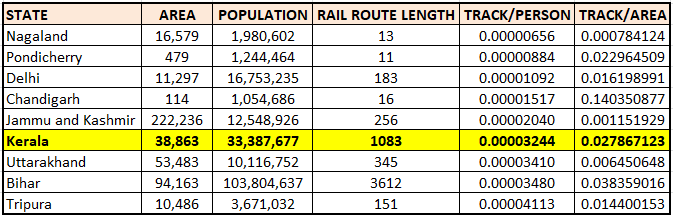

The Lowest Per Capita Track in India

Data is magic. Numbers often reveal what causes vexing problems which otherwise are difficult to substantiate. And here, numbers reveal why the railways in Kerala is such a mess. Kerala has the least total railway track per person for any state with more than 1.2 crores in population, or the lowest track density in India. This is after counting every single piece of railway track, including catch sidings and yeah, double tracks. This means that there is not enough track length available to run, park, maintain and even to rehabilitate coaches and service locomotives proportionate to the number of its people. This means fewer trains per person, resulting in overcrowding, overburdened tracks, traffic jams and infrastructure failure. The lack of track make trains wait in unending traffic jams as they crawl one behind another (at 10 minutes interval) on over utilised tracks, making it impossible to add new trains. And this is purely the result of discriminatory policies of the railways. How can track kilometres increase when doubling projects take decades, when only 123 km of new line was created since 1980 and no terminal or servicing facilities have been commissioned for the past decade? To solve rail commuting woes of the state, the very basics of railway infrastructure need to be improved with the goal of increasing track capacity to match the population of the state.

Key Infrastructure Projects to Improve Train Running in Kerala

The problem with trains in Kerala is that they are too slow and too less. To speed up trains and to ultimately run more services, track capacity has to be improved and augmented. This does not mean that we should rush to build new lines and tracks. There are a number of key infrastructural projects in Kerala’s railways, some under process for years and decades, some approved but never started but mostly never even approved or thought of. Each of these projects would improve speed and reduce running times of existing trains and ultimately allow to run more trains without substantial investment in any other hardware. They are listed below.

The Kottayam Line Doubling Project

This legendary project is often cited as the clearest and most present evidence of the railways’ inefficiency, neglect and apathy towards Kerala. The Ernakulam – Trivandrum trunk railway line splits into two at Ernakulam, and later rejoin at Kayamkulam to continue further south to Trivandrum. The older and busier out of the two, the 112 km line via Kottayam had reached 100% saturation around the year 1996. After years of struggle and clamour, the line was approved for doubling in the year 2001. It would proceed in sections with a deadline to be completed by 2008. It is 2018 now, a decade past that deadline and 17 years since the project started. And we still have 32 kilometres left to be doubled! 80 kilometres in 17 years! A massive 4.7 km per year! They took eight years to open the first 18 km of the project! The final Kuruppanthara-Ettumanoor-Kottayam-Chingavanam-Changanasserry section whose work is now in progress was approved for construction nine years ago. The deadline kept moving from 2008 to 2011 to 2015, to 2017, and now has arrived at 2020, but it surely won’t see a starter any time before 2021. That would mean 20 years or two decades to lay 112 kilometres of track alongside already existing railway track! TWENTY YEARS!! Passengers are now facing an wait of misery as newly opened tracks are plagued by speed restrictions, possibly due to faulty construction. Even if the double line were to open today, the late running would not end as traffic is now too saturated even for a double line.

The Alappuzha Line Doubling Project

The other line from Kayamkulam to Ernakulam, the 100 km coastal line via Alappuzha was first fully opened in 1991. It neared 100% saturation just a decade later (let us not talk about things like lack of vision for not constructing a double line in the first place) and was approved for doubling in 2003. It was given an ambitious target of completion by 2010. This story is equally sordid. Nine years later in 2012, already two years past the deadline for completing all of the 100 kilometres, they managed to open a full EIGHT kilometres between Kayamkulam and Haripad! The next section was Haripad – Ambalapuzha, 18 kilometres that started work in 2012. The deadline given was 2015, then moved to 2017 and now to 2018. It stands no chance of being completed before 2019. And the remaining 65 km from Ambalapuzha to Ernakulam, which is the real problematic stretch as it sees high population density with houses reaching right up to the track and also features the humongous Aroor bridge, hasn’t even been fully approved for construction yet. This line was initially intended to provide faster connectivity between Trivandrum and Ernakulam. This has now turned into a joke as trains languish for hours for crossings on the line that now serves 35 trains daily on an average. thanks to TVC’s horrendous controlling. Yeah, the usual like holding a Jan Shatabdi for a passenger train to pass. Expected date of completion: 2030. The railways, central and state governments periodically involve themselves in verbal blame game duels over who is responsible, but in the end, who is suffering?

In 2006 Southern Railway started track doubling of the 473-km Chennai-Madurai line. It was systematically completed and opened for traffic in 2018. The doubling of the 230 km Madurai-Tirunelveli-Nagercoil line is progressing at fast pace. This line sees minuscule traffic compared to the Ernakulam-Trivandrum line.

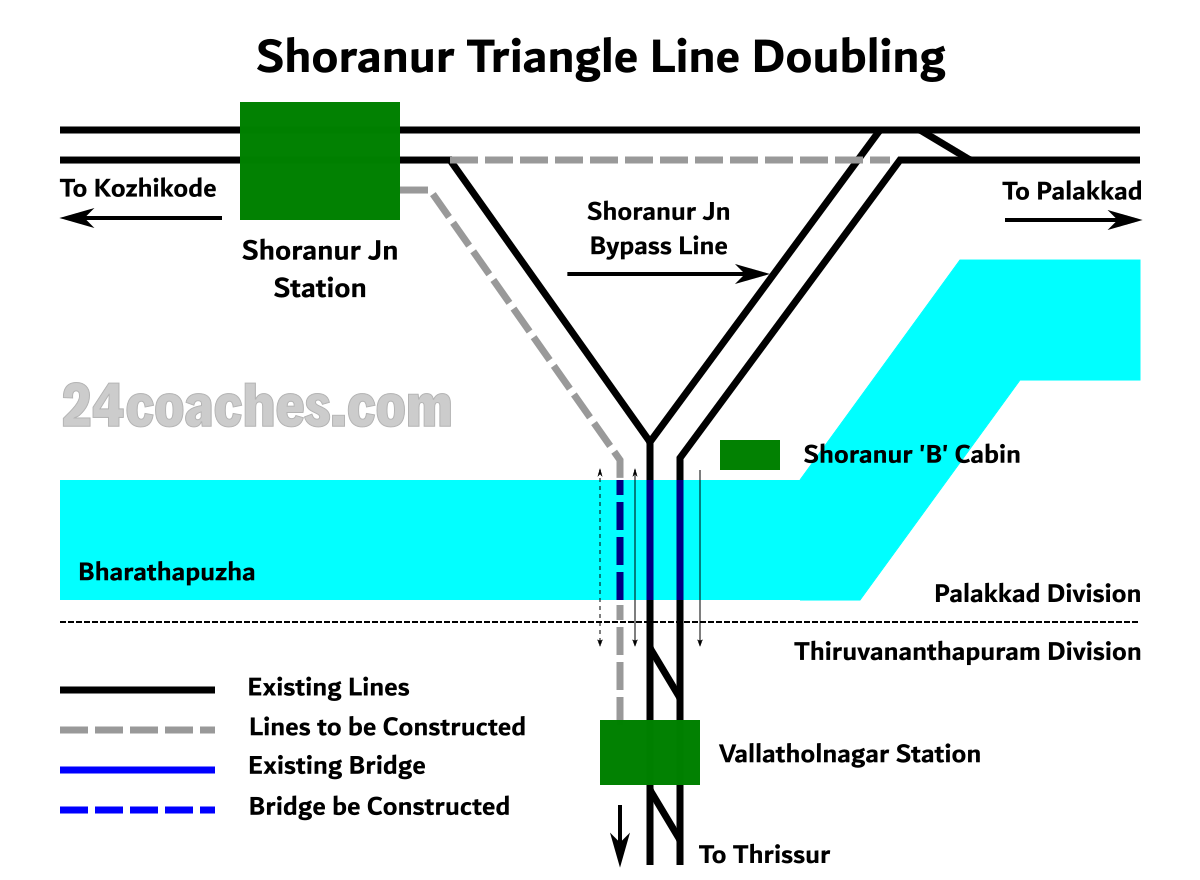

The Shoranur Triangle Line Doubling

The Shoranur Junction railway station is the largest railway station in Kerala and also its biggest bottleneck. Where the railway line from the east (Chennai/Bangalore) diverges to go north (Mangalore) and south (Ernakulam), the Shoranur junction complex is an inverted triangle with the station at its left apex, the Thrissur-Palakkad main double line as its right side, the Thrissur-Kozhikode line the left side and the the Kozhikode-Palakkad line as the top. The latter two are single lines. Those routes are fully double track for their entire length except for at this one point at the Shoranur triangle. In addition, the western bridge of the twin “double track” bridges across the Bharathapuzha river is actually a “single double line” used by both down and up trains. This is because the bottom apex of the triangle, where the line from the Shoranur station southwards towards Thrissur (left side of the triangle) meets the main double line (right side of the triangle) is located just at the bridge. There is no space to construct a point and crossing for the train to cross over to the eastern bridge. To complicate things even more, the bridge is also the crossover point between TVC and PGT divisions.

These single lines connecting the station creates an enormous crossing bottleneck. Trains have to wait at all the three apexes of the triangle to pass each other: at the station, before the bridge, at the two cabins. A train going south towards Thrissur from Shoranur cannot start until there are no trains anywhere near 10 km of the triangle! For instance, the 16649 Parasuram Express from Mangalore reaches Shoranur on or even before time on almost all days, but always starts around 20 minutes late. To allow trains to save time and run unhindered, the two connecting tracks from Shoranur station to the mainline have to be doubled. A third bridge across the Bharathapuzha along with a line until Vallatholnagar station have to be constructed exclusively for trains between Thrissur and Shoranur so the bypass route can be declogged. Once this is done, running times of most trains on this route can be reduced by atleast 15-20 minutes. However, surprisingly no such proposal has been forthcoming from neither Palakkad or Thiruvananthapuram divisions. Everyone seems to have forgotten the fact that the 200+ year old Mangalore-Chennai trunk line is not actually fully doubled yet!

Loop Line Stations and Turnout Speeds

In some stations, the train has to leave the main running line and deviate onto a side track to access the platform. Such lines are called “loop lines” and are a major cause for the increase of trains’ running times. In Kerala loop lines and turnouts (points-and-crossing) have speed limits of 15 kph. Hence when it has to stop at a “loop line station”, the entire train has to first slow down to 15 kph before the loco reaches the turnout, then crawl into the loop and to the platform at 15 kph, make the stop, then crawl out of the loop line at 15 kph and then try to accelerate back to MPS (by then it will be time to start slowing down for the next loop). Though the “official” stoppage time may be only a minute or two, a train actually loses anywhere from 10 to 20 minutes when stopping at a loop line station (A mainline station stop causes the train to lose around 5 minutes). Let that sink in. Venad’s late-running problem got worse after it was given a stop at Sasthamkotta, one of the weakest loop lines in Trivandrum division, causing its running time to increase by 15 minutes. If all major loop line stations in the state (KZK, VAK, STKT, KPY, HAD, TRTR, IJK, WKI, OTP, KTU, FK, NIL, KZE etc.) were converted to mainline stations, running times of trains would’ve been decreased significantly with no expense in land acquisition, technology etc. For instance, the Vanchinad Express now stops at 5-6 loop line stations. If they all were converted to mainline platform stations, its running times could’ve been reduced by possibly 40-50 minutes! All other turnout speeds must be increased to 30 kph from the present 15 kph.

This is also a note to those who demand stoppages of all trains at their doorsteps to satisfy their egos. The “Why can’t trains stop at the station at my door step? A one-minute stop will hardly affect the timings of the train!” argument is a great fallacy. Stops only ruin train runs. Unnecessary stoppages must be discouraged.

When this suggestion was presented once to Southern Railway, they flatly refused this too, citing again, “terrain constraints“! This is very funny, considering that in such challenging terrain as Konkan Railway and even in Kashmir, loop line speeds are as high as 45 kph! Is the terrain in Kashmir is very flat and even? Only when Kerala raises a demand do all these ridiculous problems crop up. Southern Railway themselves are constructing new stations as mainline platforms. Given that this is a sure solution to increase running times for spends of as less as around 5 crores per station, it is criminal that they are not doing this!

Automatic Signalling

How many trains can run on any given section of track at any given time depends on the signalling systems being used. Most of Indian Railways uses the late 19th-century system of manually-controlled Absolute Block Signalling. which is slow, inefficient and highly limiting. Tracks are divided into block sections 7-10 km long on which only one train can be present at any given time. It won’t be exaggeration to say that on routes using absolute block signalling, only 60 trains can be run in a day as normally a train running at an average speed of 60 kph will roughly take around 10 minutes to clear a block section. When your train is stuck at a station or on tracks for extended times, it is mostly only waiting for the train ahead to clear. Kerala is at that stage now. Tracks feature almost one train per block at most given times, resulting in virtually no gap (path) to run new trains anymore. Yes, on double tracks. The only way to run more trains now is to upgrade the signalling system to Automatic Signalling used on suburban sections (Mumbai, Chennai, Kolkata etc) and on high-speed and high-density routes (Delhi-Agra, Chennai – Jolarpettai etc). Automatic block signalling also uses blocks, but sub-divides them into many smaller blocks of 2-3 km. Train movement and signalling are all controlled by computers. Automatic signalling will increase track capacity by atleast three times as it allows more trains to be run with greater frequency.

However, Southern Railway flatly refuses to even consider implementing Automatic Block Signalling anywhere in Kerala! If the Chennai-Jolarpettai section with 53 trains can be allowed automated signalling, why isn’t the Kayamkulam-Kollam section with 83 trains and the Ernakulam-Thrissur section with 91 trains running 330 services a week (one side) be allowed automatic signalling? Their excuse here is “terrain”, for some reason. Automatic block signalling itself is hardly new technology. It has been in use in Europe and USA since the 1960s including in railway systems in the Alps. What was the terrain constraint, again? Automatic block signalling should be the least used everywhere on the Indian Railways. In fact, most railway systems in the world have abandoned it to move towards more modern systems like CBTC and ETCS (used on Indian Metro systems).

If Indian Railways and Southern Railway were to complete these projects, the running times of all trains in the state could be easily bought down by 30 minutes to 1.5 hours! This is without any additional land acquisition (other than what is already required for the doubling of the to lines. It would help the general public save a lot of time and money and improve the well-being of the people. However, no one seems to be interested in things like that. Going ahead come the big boys. To improve the railway track to person ratio and to enable more trains to be run in the state, it is imperative that new railway lines be built. A number of new tracks, routes and lines were announced over the years, construction of some of which had started, but most haven’t. Some of these routes are imperative for any kind of development of the state in the fastest and most environment-friendly way. The next chapter in this series will deal with the state of new railway lines in Kerala.